Autumn is here. The broomsedge and goldenrod grow tall, and the oak and hickory shed their foliage in green, red, yellow, and brown confetti. I can hear the thump of plump pecans when they hit the ground and the sharp ping of the acorn as it hits the tin roof of my garden shed. There is the quiet scratching of claws on tree trunks, and the chipper of squirrels as they notice me. All of this happens in the warm shimmer of filtered, amber light, and if I get too warm, I can count on a sharp, cool breeze to bring me back to comfort. When I wonder if I’m in paradise, I remember that I am.

I mean this quite literally, I am not waxing poetic. The modern English word paradise derives from the ancient Greek paradeisos, which was used to describe the walled gardens and enclosed royal hunting parks (or pairidaezas) found throughout the ancient eastern Mediterranean and Western Asian worlds.

Paradise gardens are typically enclosed by walls or tall fencing, and plants are selected and cultivated for their beautiful blooms, attractive scents, or edible fruit, and usually contain some element of water, such as a small pond, pool, or bath for birds. This specific type of garden originated in the ancient Persian empire during the Achaemenid Dynasty (559 – 330 BCE), but the idea of cultivating an outdoor space for pleasure and leisure, rather than food and subsistence became a marker of class. And, gardens aren’t just about what is in it, but often who or what is being kept out of it, in terms of access and ownership.

It wasn’t until the word was adopted in the Greek Old Testament that it acquired its holy, supernatural connotations and its association with the Garden of Eden, but even then, these origin stories remained rooted in ownership, exclusion, and control. As Robin Wall Kimmerer writes of Eve in Braiding Sweetgrass,

“For tasting its fruit, she was banished from the garden and the gates clanged shut behind her. That mother of men was made to wander in the wilderness and earn her bread by the sweat of her brow, not by filling her mouth with the sweet juicy fruits that bend the branches low. In order to eat, she was instructed to subdue the wilderness into which she was cast,” (7).

Paradise by the Artificial Outdoor Flood Lights

That idea of a paradise garden has followed us across time, from ancient Persian gardens to our modern-day backyards. We plant lush turf, build fences, and maybe put in a pool. We trim our perimeters with exotic ornamentals, evergreen hedges, and shrubs for winter color. But, these things provide little ecological value, and and in many ways actively harm the environment.

Lawns are the #1 irrigated crop in America, and they feed no one and provide nothing, plus mowers guzzle gas and pollute the air. Not only is turf not beneficial, it actively creates water problems. Turf has a 75% runoff coefficient; instead of absorbing rainfall and reintroducing it back to the water system, the water runs off to storm drains. That is, unless there is a particularly heavy rain or a blocked drain, in which case you get flooding.

The truth is that uniform green lawns and vibrant blooms of ornamentals may look alive, but they are comparatively dead when you consider the biodiversity of plants and animals native to the area.

The insects, rodents, and other “pests” Americans spend millions trying to evict from their backyards are unwelcome at best and perceived as a threat at worst. These tiny, often helpful neighbors of ours are treated like dangerous criminals who must be exterminated for having the audacity to simply exist alongside us. Over the past forty years, we have lost 45% of the global insect population and many scientists agree we are in the midst of the sixth mass extinction. But, pesticides are only part of the problem, insects need food and shelter, too. Each year, they have fewer places to eat and even fewer places to breed. Many species have a very narrow range of plants they or their larvae can eat and their foraging excursions are useless, anyway, as native grasses and plants are doused with chemicals, pulled up, and replaced with turf.

Plus, this curated idea of paradise is not just ecologically barren—it is also built on stolen ground.

For Glory, God, and Gold!

The land I live on is old, even though the “history” attached to it insists on a much later origin. In the past forty years or so, enough re-education has been done that most people acknowledge that the Spanish empire committed genocide in Central and South America, leading the way for a bloody land grab on an entire hemisphere. And, while Christopher Columbus had his national holiday reassigned as a day of remembrance for the civilizations and cultures destroyed in his name, there is much work to be done in terms of education and reparations.

The Europeans didn’t stumble upon a virgin wilderness. In fact, quite the opposite. What they found instead was a thriving continent of connected cultures. Complex roads, trade networks, and sophisticated agricultural techniques. The forests of the East coast of the modern day U.S. were far more “wild” in the nineteenth century than they had been in the seventeenth century, because the Indigenous people that managed the land for centuries used burns and forced migration of buffalo to turn forest into farmland.

I knew that the county I grew up in was once home to the Cherokee, and the Muskogee, or Creek, people. Just two miles from my home are the Etowah Indian Mounds, remains of the Mississippian culture that inhabited the area from around 1000 CE to 1550 CE. Recent discoveries have suggested that the ancestors of the Mississippian “mound builders,” migrated out of central Mexico.

In 2010, less than 5 miles away from my home, an ancient site was unearthed that contains evidence of the Ladd’s Mountain Observatory, a ceremonial astronomical site that dates back to 300 B.C. The investigation has revealed that this site may have been a major center of worship and a crossroads for travelers throughout the Southeast and Midwest.

“It was a remarkable example of Indigenous architecture that is virtually unknown among archaeologists in North America outside its immediate environs . . . a complex oval stone structure on a mountain top overlooking a four-mile-long continuous conurbation of Native American towns and villages. In Europe or Latin America, it would have been restored and promoted as a spectacular tourist attraction with a “million dollar” view. However, in mid-20th century Georgia, it and a stone mound on a terrace beneath it were crushed into gravel to repave a nearby state highway. In the proposed path of this highway were three large mounds, almost 2,000 years old. They were used as fill dirt for the highway.” – AlekMountain, “Ladd’s Mountain Stone Observatory,” The Americas Revealed, (June 2019).

As the writer of this blog states, this structure was extremely significant and the fact it was destroyed to make gravel for a highway tragic. They quite literally paved paradise to put up a parking lot.

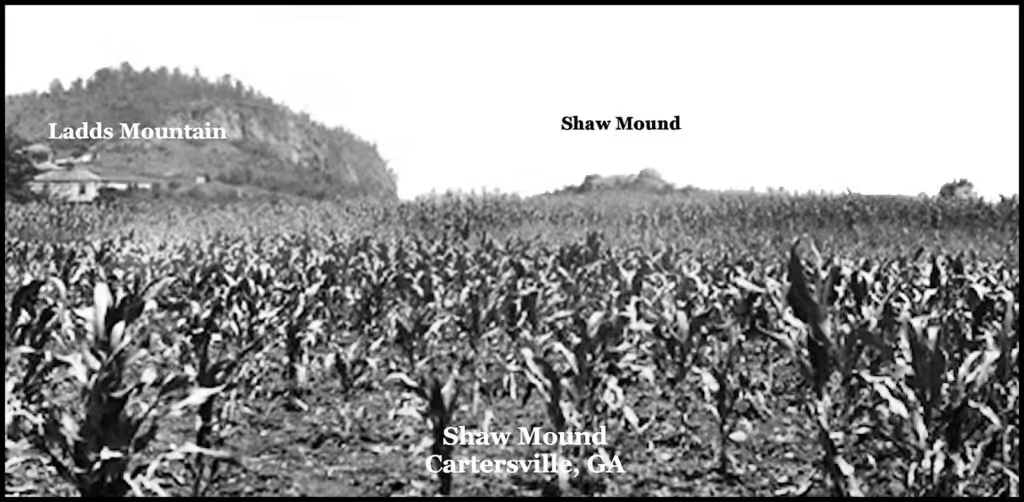

The most haunting part of this discovery for me is this image of the Shaw Mound. This stone burial mound was dismantled around 1940 and repurposed as more gravel for Highway 113. From, The Americas Revealed,

“The Shaw Mound was a stone burial mound at the foot of Ladds Mountain that was dismantled circa 1940 to collect the stones for road fill and to satisfy the curiosity of the landowner. A single individual was found within, buried with several items of copper, including a celt (axe), breastplate, and a cutout; large sheets of mica atop the face and chest; and stone celts. Scraps from the production of such items are abundant at the nearby Leake site. A very frustrated archaeologist with the National Park Service, Calvin Johnson, watched as the stone mound was dismantled by laborers and loaded onto dump trucks. He found a royal burial with copper and stone artifacts as the base. No one knows what happened to the skeleton of an important male leader after he excavated it.”

I’ve gazed upon the broken face of Ladd’s Mountain hundreds, if not thousands of times, from this exact vantage point. Now, beneath the mountain are fast-food restaurants, a supermarket, and a carpet factory named Shaw Industries.

By the time Georgia became an English colony the remaining Muskogee had been terrorized out of the region. If there is reliably sourced Indigenous history written about this county, I’ve found little of it. What I have found relies heavily on whitewashed historical narratives. From the Etowah Valley Historical Society,

“With the arrival of Europeans, Native Americans severely suffered from the diseases brought by the explorers. Lack of immunity to European diseases eventually caused the greatest deaths to the Indian population and not warfare.”

As Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz explains in An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, the idea that it was epidemic disease, and not genocide, that reduced the Indigenous population of the North American continent by 90% is patently false. By the time the settler-colonial states of Spain, Great Britain, and Portugal made their way to the Americas, they were already experienced in terrorizing people into economic dependency and slavery and eradicating their culture, such as the British had done in Scotland, Ireland, and Wales.

Thus, “if disease could have done the job, it is not clear why the European colonizers in America found it necessary to carry out unrelenting wars against Indigenous communities in order to gain every inch of land they took from them,” (40). These were colonizing projects and biological warfare was a part of it.

Again from the Etowah Valley Historical Society,

“The Cherokee were the most adaptable and best assimilated of all the Native Americans to the encroaching white explorers. They adopted white customs, converted to Christianity, developed an alphabet, practiced a democratic government and owned land.”

This is quite a rosy view. And despite this, in 1837, these “easily adaptable” folks were forcibly removed from their homes and driven westward along what came to be known as the Trail of Tears—a brutal journey marked by starvation, disease, and death, to Oklahoma. Thousands perished along the way, as the U.S. government sought to clear land for white settlers and expand its dominion.

Facing Uncomfortable Truths, Restoring the Heart

I recently took my daughter, who is almost three years old, to the Etowah Indian Mounds. Even though I drive by them daily, I haven’t been since I was not much older than her on a field trip with my elementary school. I remember not being able to go to the top of the big mound because there were bees. The view from the top is breathtaking (if you face away from the power plant and the trailer park). Looking down, she said, “It’s Te Fiti!” and my heart melted.

Te Fiti is the personified and fictionalized island in the Disney film Moana, and I can definitely see where her little brain made the connection. If you haven’t cared for a child in the past six years, here is a brief synopsis of the film. Moana is the teen daughter of the Chief of Montinui, a fictional Polynesian island, and she is poised to be the next chief. Her island is facing food shortages, but they will not travel into the open water because “no one goes beyond the reef.” Moana has always been drawn to the sea and learns from her super cool grandmother that their ancestors had once been sea voyagers (wayfinders) until the demigod Maui stole Te Fiti’s heart, turning her from a fertile, verdant, life-giving Mother Island, into a demon lava monster that sinks ships. Moana is chosen by the ocean to restore Te Fiti’s heart, and she does. There are many wonderful lessons in this kid’s film and a great many parallels to the stories I’ve just told about paradise– theft, ownership, resource management, and responsibility.

What I plant, and how I plant, reflect these deeper stories. The more I learn about how to steward this land, the more I have to face these uncomfortable truths—about pollution, colonization, and my complicity. But that discomfort is a chance for growth.

By embracing native plants, resisting pesticides, and letting nature take the lead, I can create a more genuine, reciprocal paradise, at least in my own backyard. We can restore the heart. Learning our history opens our eyes to the injustices woven into our landscapes, and the paths available to resolution and reparations.

Gardening for me, is becoming not just an act of cultivation and regeneration, but one of revolution and reclamation—of both land and power, in a world that is in desperate need of both.

You are such a talented writer! Can’t wait for the next article!

Thank you!

Your blog is a testament to your expertise and dedication to your craft. I’m constantly impressed by the depth of your knowledge and the clarity of your explanations. Keep up the amazing work!

Thank you so much!

Fuck yea, that’s my sister! You captivate the reader like no other! What I thought was a script of the backyard took me on a historical whirlwind of the land I grew up, and also, a different view from a better window. Thank you for the read. I love you!

Pingback: The Revolution Will Not Be Fertilized - fullbushgardening.com